SKBA Newsletter February 2023

- New SKBA Website

- Coming Events

- Co. County declare Kildare a Native Honeybee Conservation Area

- ‘What we can learn from Wild Honey Bees?’

- Looking into Hedgerows

- Professor Jane Stout (botanist) – ‘Countrywide’ Interview

- Plea for Readers’ Articles, Photos etc.

New SKBA Website The new Club website has been up and running since late January. After some teething problems, it is now functioning well and includes notifications of meetings, events, facility to pay membership fees, beginners’ course fees, dates etc. Further functions will be added soon. The Committee has put in a lot of time into the tedious technical work involved in the new website.

Coming Events

• Beginners’ Course starts on Wed. Feb. 15th, 7.30pm, Athy C of Ireland Hall.

• Dail Protest Against Hedgerow Destruction at Leinster House, Wed. Feb. 15th between 12.00 and 1pm. Organised by Hedgerows Ireland and an alliance of organisations, including beekeepers, farmers and many individuals.

• Carlow Beekeepers Association, CBKA, hosting a talk on Using Nucleus Hives to Support Your Beekeeping in SETU Carlow, Haughton Building, at 7.00pm, Mon. Feb. 20th. Free parking in designated parking spaces. SKBA members invited.

• The Native Irish Honeybee Society (NIHBS) AGM starts at 7.00pm on Mon. Feb 27th. Members of NIHBS can attend virtually through Zoom. There will be a talk on Honey Production with Native Honey Bee (Eoghan Mac Giolla Coda).

• Report from Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity (2022) expected in coming months.

• SKBA’s next meeting, 7.30pm, March 1st (first Wednesday of the month).

Co. Kildare: a Conservation Area for the Native Irish Honeybee (Amm) On December 19th, 2022, Kildare Co. Council passed a formal motion and took the first step in declaring the County an area of conservation for Apis mellifera mellifera (Amm) or the native Irish honey bee. Loretta Neary and a group from NIHBS made a presentation to the full Council Meeting. Paula O’Rourke, Climate Action Co Ordinator for Kildare CoCo, was very impressed

What We Can Learn From Wild Honey Bees As is customary with the SKBA, each club meeting features a talk/lecture or demonstration. At the recent February meeting, the Committee put on a screening of Dr. Grace McCormack’s lecture at the National Honey Show in London in 2022: ‘What we can learn from Wild Honey Bees’. Watch on YouTube at: https://youtu.be/kRywONwvSnE The National Honey Show is a big annual event in the calendar of British beekeepers. Some Irish beekeepers attend and are successful in the honey competition. Grace McCormack (NUIG) was one of the lecturers.

Summary of Dr. McCormack’s lecture:

Honey bees are, first and foremost, a wild species. Sometimes they are described as domesticated but that is not correct: we cannot control what the bees eat or how they mate. The best words to use might be ‘beekeepers manage’ or ‘semi-manage’ bees. Beekeepers have a great responsibility in managing bees. Beekeepers wouldn’t have health and diversity in the managed bees without the bee population that exists in the wild. Grace has been sampling bees that live outside of apiaries since 2015. Academic studies on the genetics of bees have been carried out and one study by —— in 2010 indicated the existence of bees other than the bees sampled from apiaries. What do we call such bees? Some say ‘feral’, others say ‘wild’. Grace and her colleagues refer to them as ‘free-living’. She said that we don’t know if or when they have escaped from apiaries or when, more likely, their ancestors have come to and gone from apiaries. We know that they can live, unaided, in the wild. Hence her preference for calling them ‘free-living’ bees. Grace and her students contribute their data to the National Biodiversity Data Centre and have set up an online form for people to report locations of free-living colonies. She urged people to report sightings of wild colonies. https://records.biodiversityireland.ie/record/ wildhoneybeestudy Because Ireland has, regrettably, fewer trees than the UK, most of the 500 reports submitted refer to nests/hives in the roofs of houses, ruins and churches. There’s much work yet to be done in finding bees in Ireland’s National Parks. Grace has been working with academics in the UK who have been studying free-living bees in Blenheim (Winston Churchill’s home) and Boughton Estates where some of the oldest oak forests in the UK are located. A high degree of hybridisation has been noted but the Boughton Estate has a high proportion of Apis mellifera mellifera (Amm), the original native black honeybee of Western Europe. She has sampled wild bees in Donegal, a county that had escaped varroa up to recently. A Dutchman has been creating and placing carved-out logs for wild bees in Donegal.

Grace and others have noticed that the colonies of hybrid bees (imported bees crossed with native black bees) are not as healthy as the darker, blacker native bees (Amm). Many do not survive winter. Of the 76 wild colonies she has been tracking with the help of beekeepers since 2016, 14 are still going strong and she is pleased with them. Using a genomic approach, an overview of the genes in each bee sample, Grace has been sampling and examining a small number of wild hives. She has noted a strong survival rate in certain colonies (Spiddal, 2016-2020) with a similar lineage over a four-year period. She considers samples of 30 or more bees to be necessary for her work. Her team has been gathering evidence that bees are mating locally and, as a result, there are clusters of colonies of similar genes in different regions in Ireland. Hence, there appears to be distinct bees in Donegal, distinct bees in Connemara, Louth, Tipperary, etc. The IUCN (The International Union for Conservation of Nature) couldn’t, in 2014, determine if there were bees in Europe other than managed bees. Grace and others are accumulating data to enable the IUCN to recognise the existence of distinct, wild bees in certain parts of Europe. Grace reported that, according to a survey, about 90% of Irish beekeepers claim to keep Irish black bees (Amm) and that more and more Irish beekeepers are not using chemical treatments for varroa. She is opposed to the use of chemical treatments in beekeeping, maintaining that beekeepers cannot expect farmers to stop using chemicals if beekeepers themselves use them.

She agrees with Tom Seeley (New York) that untreated and unmanaged bees can become a source of varroa-tolerant/resistant bees.

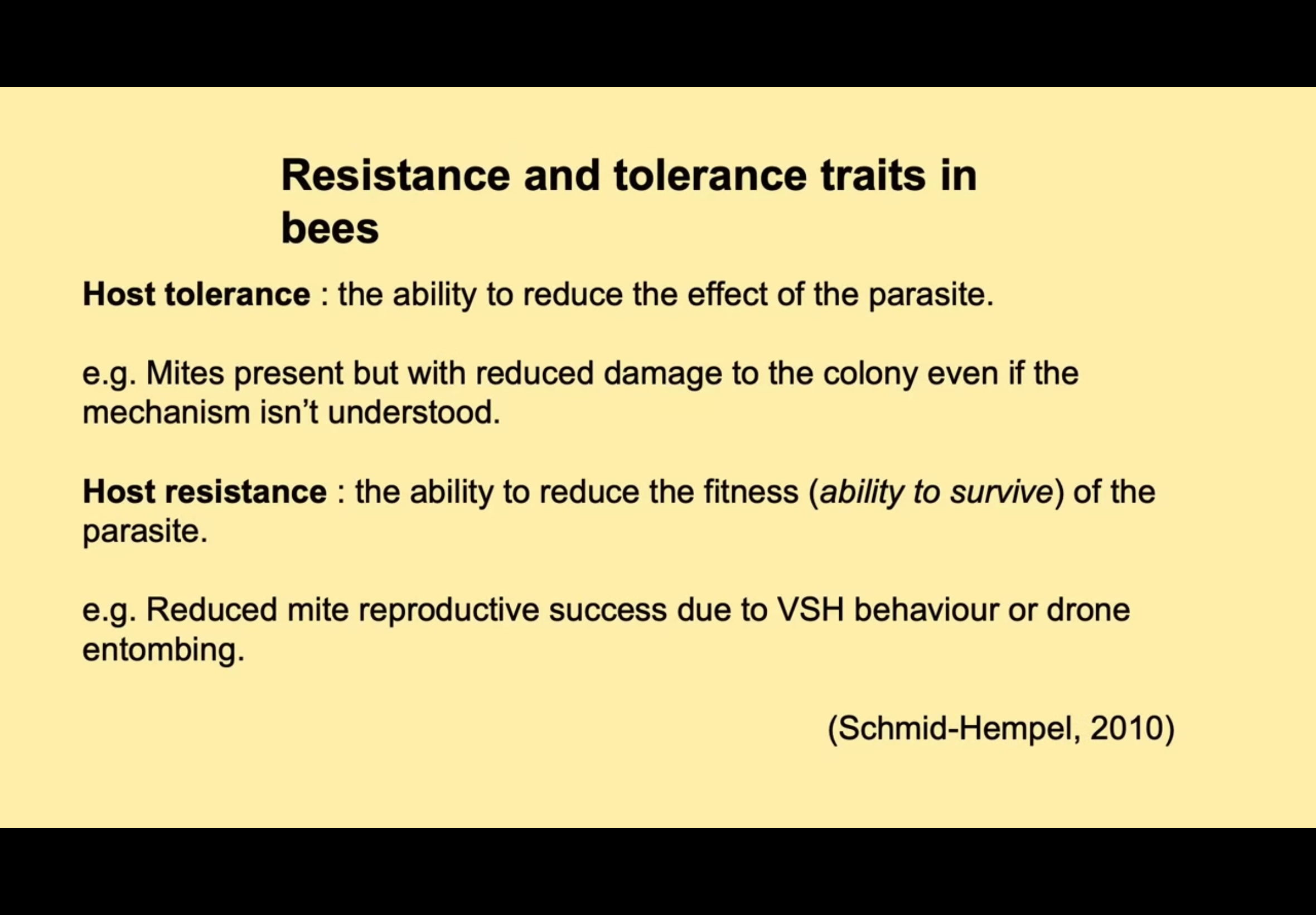

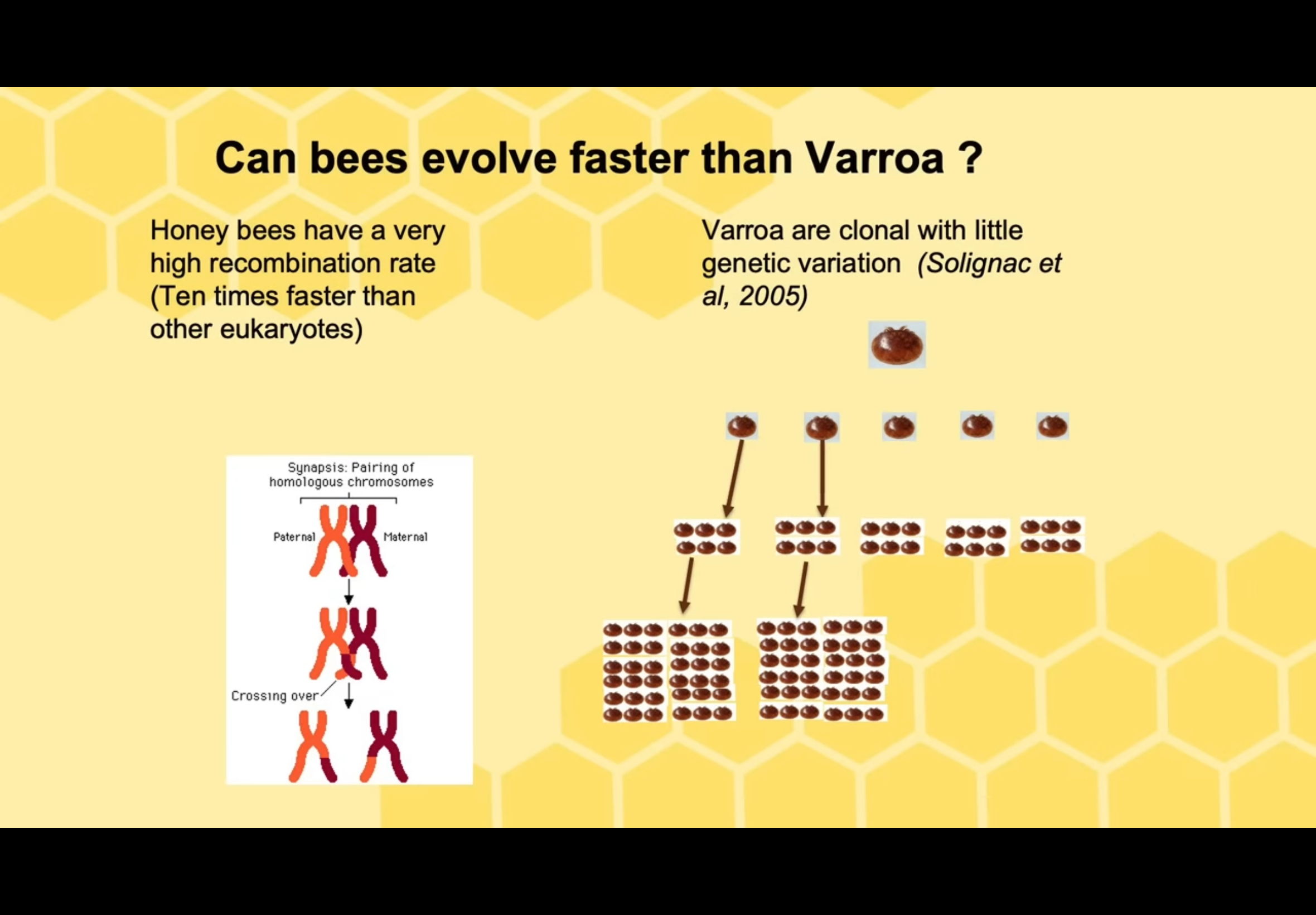

Grace supports her view that honey bees, as host, can adapt and survive the varroa mites, parasites, by explaining briefly how the bees, when sexually mating, pass on genetic material from both parents to their offspring, thus changing quickly from generation to generation. The mites, on the other hand, do not change much over time as their reproduction is clonal. The traits that enable the bee to survive are passed on through generations – Darwinian selection.

The practice of beekeepers independently treating weak colonies to keep them going is not good practice. She stresses that beekeepers should, instead, help each other out when a fellow/local beekeeper’s bees are failing. Beekeepers should collaborate locally and within clubs. Finally, she pleaded that beekeepers to not feed sugar syrups to bees but to leave them more of their own honey. Beekeepers do well with the bounty that bees provide.

Discussion after video

Our Chairman, Louis, advised the audience, especially the beginners, not to be daunted by much of the content of the video. He advised that beginners can start learning how to keep bees without understanding much of the science involved in this video. The beginners present were very enthusiastic about the video. One lady expressed her determination to start beekeeping with black bees and asked where she could get them. The more experienced beekeepers present had to be impressed by Grace McCormack’s enthusiasm, energy and pioneering role in this field of study.

Photo: Pat Gartland’s lovely black bees getting some fresh air on Christmas Day

Looking into Hedgerows

It’s mid-February and, like Michael Harding, I’ve been looking into hedges a lot recently. The Birdwatch Garden Bird survey, at which I’ve been trying my best for the past eight weeks, has shown me how little I know about our birds. There’s a lot of uncertainty and guesswork in what I submit to the survey: Is that a song thrush or a mistlethrush? A bullfinch or a chaffinch? Blue tit or great tit? The early sunlight seldom helps me with identification. I tried using my binoculars a few times but found that they are of little benefit. Thank God that there are still lots of birds in our garden hedges. But will our Irish hedges continue to hold wildlife? We have to be concerned. Hedges are the highways of life in the Irish countryside – that’s a bit of a cliche – but it does express the the continuity of the activity of all the hedge’s creatures, backwards and forwards, through the whitethorn, blackthorn, hazel, gorse, brambles and many other trees, bushes and wildflowers. Beekeepers have to be concerned about the continuous decline of Ireland’s hedgerows. Honey bees are increasingly dependent on foraging in hedgerows with so many fields used for monoculture – growing a single crop such as a grass or a corn crop. The continuity of hedges has been and continues to be broken in so many ways, especially for the expansion of pastoral and arable farming. The non-farming community have been removing hedges that bound gardens and building sites for a long time. Why? For the sake of a tidy appearance? Natural hedges and their habitats have been replaced by concrete walls, panels and non-native plants that cannot host our native flora and fauna or sustain the ecosystems of Irish hedgerows. Lawns, another form of monoculture, are of no benefit to wildlife. Worse still, lawns are often treated with chemicals.

Leadership Role for Beekeepers?

Beekeepers are generally held in high esteem in our society. Their craft and knowledge are viewed with awe by so many people. The real mystery is, of course, the bees themselves. Beekeepers must play a role in addressing the many threats to hedgerows and other wildlife habitats. They must give good example in the practice of their art and explain to the public just how serious the loss of flora and fauna has become. In fact, as Dr. Jenny McElwaine, eminent botanist, said at the final weekend of the Citizens Assembly on Biodiversity, the word ‘loss’ is too gentle a word. ‘Loss’ suggests that what has been lost can be found. Society needs beekeepers, and many others, to spell out the critical point at which our natural world is poised. According to Hedgerows Ireland, the Dept.of Agriculture allows a landowner to destroy up to 0.5 km of hedgerow without any environmental assessment or permission. This organisation estimates that 3000 km of hedgerow is removed every year: https://hedgerowsireland.org/&usg=AOvVaw3U3VMQ5fgtBqmu6vqROcCU

Professor Jane Stout Interview

Philip Boucher-Hayes took over presenting ‘Countrywide’, on RTE Radio1, about three months ago and during this time he has brought environmental matters to the fore in this magazine-type programme. We need journalists, such as Boucher Hayes, who will keep challenging all of us to be active in addressing the major issues of our time.

What follows is a transcription of an interview from a ‘Countrywide’ episode in early December, 2022, during the fortnight of COP15, the Montreal biodiversity meeting.

Prelude to the interview: ‘We are treating nature like a toilet. The loss of nature and biodiversity comes with a steep human cost. This conference (COP15) is our chance to stop this orgy of destruction. No excuses. No delays. Promises made must be promises kept.’ – Antonio Guterres, United Nations Secretary General, addressing the COP15 assembly.

Interview with Professor Jane Stout, Botany Professor in Trinity College – (co-founder of the All-Ireland Pollinator Plan)

Philip B-H: Why is the biodiversity crisis as deserving of our attention as all the other crises, especially the climate crisis?

Prof. JS : When we talk about biodiversity, we talk about it being a life-support system.

We are talking about the food we eat, the air we breathe, the water we drink. All of these are a result of the ecological system that we are part of. All of the changes that are happening, social, political and climatic, risk and threaten our biodiversity. Decline in biodiversity, in turn, threatens the provision of food, fuel, shelter. The World Economic Forum now puts the decline of biodiversity as one of the top three global risks to businesses. Biodiversity is not just a nice thing to have…….It is fundamental to our existence.

Philip B-H: There is a nice-to-have and very easy-to-read report card on Ireland’s biodiversity: Ireland’s National Biodiversity Index which is (depicted) in terms of a traffic-light system…….there’s a lot of red and a lot of amber in there, few greens. (See website: National Biodiversity Indicators: Ireland 2020 Status and Trends)

Prof. JS: Yes. Most people don’t realise how serious the situation is. We step outside the door and there’s still trees, still lots of greenery and birds. We don’t notice this slow erosion of nature …..It’s very concerning.

Phillip B-H : There are more than 30,000 species (animals and plants) in Ireland. We have only assessed a small number of these species under the national framework.

Prof. JS: We have assessed, nationally, only about 10% of our species in Ireland. Of those we have assessed, one in five are at risk of extinction. That’s a very sobering statistic. In order to assess a species, we need a huge amount of information about where they are, how they are faring etc. For most species we just don’t have that information.

Philip B-H: Of those species we have assessed, about 3% are ‘regionally extinct’. What does that mean?

Prof. JS : ‘Regionally extinct’ means they are no longer found in Ireland but they still exist elsewhere on the planet.

Philip B-H: 15% of the 10% that have been assessed are ‘critically endangered’. And a further 9% are ‘threatened’ status. That means that almost one third of the species we, in Ireland, have assessed are somewhere on the spectrum between ‘regionally extinct’ and ‘threatened’. That’s a very grim picture.

Prof. JS : Now, when we speak about biodiversity we are usually speaking about species. But we must remember that biodiversity is more than just about different species. It is also about diversity of habitats and ecosystems. So, as we lose habitats and ecosystems or as habitats become smaller or more separated, then we lose the population of species that live in them.

Philip B-H: Can we get the benefit of (part of) your area of expertise: insects? So many bumblebees and butterflies are endangered?

Prof. JS : One of the difficulties about insects is that they are very mobile and they are quite difficult to survey. Assessing numbers and tracking changes in numbers is very difficult. With the All-Ireland Pollinator Plan, we’ve been trying hard for the past seven years to reverse the decline of pollinators, including bumblebees and butterflies. We don’t have enough data to say if we are succeeding. However, we have seen an increase in the number of areas and amount of areas that are being managed in a pollinator-friendly way. We have seen a huge increase in awareness and effort on the part of farmers, local communities, businesses and councils.

Philip B-H: Should light pollution be considered a threat to biodiversity?

Prof. JS : Yes. A lot of animals are affected by light. Light can disrupt their activities. In terms of insects, moths are active at night and their foraging behaviour 9 and their reproductive behaviour can be disrupted by light. Moths, of course, are also pollinators. Different kinds of light, depending on the wavelength of light, affect different animals. Again, this area is difficult to examine.

Philip B-H: Would an agreement at the COP15 (UN Biodiversity Montreal Meeting), like the Paris agreement for addressing climate change, make any difference?

Prof. JS: If there’s an agreed global framework at COP15, then it would bring it up the political agenda. It would, hopefully, help with the enforcement of environmental laws that are already in place. It would help protect biodiversity and the rights of indigenous people (such as native tribes of the forests in S. America). Hopefully it would see biodiversity policies integrated into other policies such as the agriculture policy, forestry policy etc.

Philip B-H: Does climate policy generally get more attention and action than biodiversity policy?

Prof. JS : There is a danger of tunnel vision with just looking at carbon emissions. We need to be aware that some actions which attempt to reduce carbon emissions can have a negative effect on biodiversity. We need solutions that tackle both global problems.

Philip B-H : A farmer, on this programme some weeks ago, said that farmers don’t know a lot about biodiversity but they know what nature is. Would it be fair to say that the biggest agents of potential change here are farmers?

Prof JS: Yes. The farming community does an amazing job in protecting a lot of our biodiversity. They are custodians of biodiversity for the future. And they care about nature. But sometimes the policy instruments and the tight margins under which they are working don’t allow them to do what they would like to do perhaps. And some of the policies in the past have been destructive of biodiversity …….At the moment, farmers, rightly, are saying that if we want farmers to protect biodiversity then farmers should be compensated. And that’s fair enough.

The SKBA Newsletter needs your articles, stories, photos. For instance: Irish summer drought and the bees Garden ponds – sustainable management, safety, costs Gardening for biodiversity – flowers, trees Any story, personal experience, long or short, relating to beekeeping, gifting honey, photos of bees foraging, swarming etc.